or: dealing with “problem finders” in companies

How we deal with problems, both in the company and in society, reflects who we are as individuals. However, how we deal with people who draw attention to problems says a lot more about us.

At this point I have to confess: Yes, I am a pessimist! Or at least what is colloquially known in professional life as a pessimist.

When I read Henning Beck’s LinkedIn post, I realized how often I talk about problems instead of challenges, about competitors instead of rivals, in my everyday life and in my professional environment. I’ve noticed for years that – not just in marketing, but in business in general – we tend to gloss over language. We tend to change the vocabulary to avoid the word “problems” and try to portray everything as a “challenge” and a “learning”. At the same time, however, I often see in the background how companies are struggling with internal difficulties: Processes don’t work, teams work together inefficiently and there are human and professional “challenges” everywhere. Nobody dares to utter the word “problem” or a comparable synonym. Employees who point out problems [sic!] are held in lower regard than employees who present (supposed) solutions.

Friends once said about me that I give answers to questions that no one has asked. As a young person, I was unsure what exactly that meant. Today I would ask why no one has ever asked these questions!

Naggers vs. uncoverers

Nowadays, when employees point out mistakes and say: “Guys, there’s a problem here. Take a closer look.”, they are quickly labeled as pessimists, complainers or doubters. It gives the impression that you are only capable of pointing out problems rather than finding solutions.

This is why one of the classic career and/or rhetoric tips is always:

Bring in solutions, not problems.

[quote in german]

Nevertheless, I am firmly convinced that it is necessary to put our finger in the wound, call a spade a spade and point out the problems in order to be able to solve them. I am convinced that this has nothing to do with classic pessimism or nagging. Rather, it means clearly addressing the problem and still looking for solutions – alone or in a team. In my opinion, anything else is “pie-in-the-sky optimism”, which only serves to avoid being labeled a “grumpy pessimist” and a sourpuss. True to the motto: “Tchakka, you can do it!”

Calling a spade a spade means getting to the root of the problem

The article by Marco Müller is also fascinating:

[quote in german]

Antonia Götsch, Editor-in-Chief of Harvard Business Manager, also addressed precisely this problem in her LinkedIn article “Anyone else a member of the solutions fire department?”.

[quote in german]

Better to think for 30 minutes than to work wrong for a day

“Nothing is worse than doing the wrong thing right” (loosely based on Mirko Lange) or walking at full speed in the wrong direction. It’s better to study the map a little longer beforehand and then walk slowly in the right direction.

Thomas J. Watson Jr, former IBM chairman, is said to have once said in a management meeting:

[quote in german]

Thoughts are the key to success. One employee thinks more than another. It is important to use this energy and commitment instead of suppressing it.

Depth of explanation (IOED), the “Rule of 10” and how to talk to ducks

Three themes struck me while researching this article. Firstly, the term:

1. “IOED”

The acronym describes the tendency to believe that we have understood a topic, although on closer inspection it becomes clear that our knowledge is superficial and we cannot explain the topic in depth. But instead of talking about overconfidence, the focus of this article is on finding solutions rather than analyzing character traits.

Too often we succumb to the illusion that we have understood the essentials, while the details escape us.

An example from the source illustrates this: Many people know that a refrigerator cools, but few can explain exactly how this works technically.

[quote in german]

2. Rule of ten – questions are worth their weight in gold/money

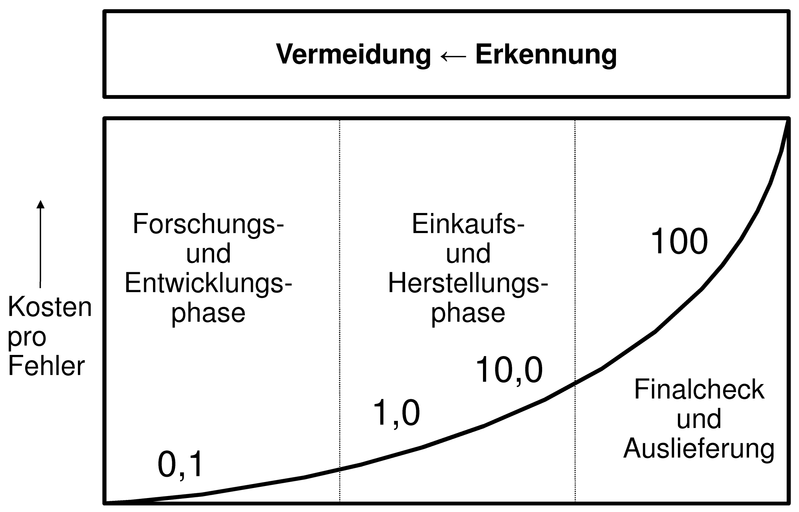

A second important point, which I didn’t know by name until my research, is the “Rule of Ten”. Simply put, it means that the earlier a problem is identified or a question is asked in a project, the lower the costs caused by that problem. Conversely, the later a problem is identified in the course of a project, the higher the costs.

[quote in german]

Answering questions or asking questions yourself means not only responding to existing concerns, but also identifying and preventing potential problems at an early stage. This is essential, as rectifying problems in advance is much more cost-efficient than making corrections after the fact. And so “answers to questions no one has asked” are really just identifying issues and problems at a stage when they can still be corrected cost-effectively. (Source)

You’re one right question away from a breakthrough.

3. Rubber duck debugging: solving problems yourself

I found the “Rubber Duck” method funny and interesting.

Rubber duck debugging is a technique from the programming world that aims to solve problems independently by formulating and explaining them in detail. Instead of immediately asking for help, it can be more effective to organize your thoughts and describe the problem in detail. This method can not only save time, but also improve your ability to help yourself. Below we explain how you can apply this technique in five steps.

a.) Put the problem into words

It often helps to simply put the problem into words. This can be done verbally or in writing.

b.) Add details

Explain what happened before the problem occurred and what steps you would take if the problem cannot be solved.

c.) Clearly formulate the goal

Explain not only the problem, but also what you want to achieve. What is the desired outcome and why is the current situation unsatisfactory?

d.) Share your own research

Before you ask questions, you should carry out your own research. Share the results of this research to show what solutions you have already tried.

e.) Ask the question

If you have not been able to solve the problem yourself despite all the steps you have taken, you now have a well thought-out question that you can ask colleagues or in a forum. (source)

This method is certainly not applicable to all teams, sectors and employees. The method must be learned, practiced and desired. And this method could certainly also be covered very well by AI.

It would be worth a try.

A sign of intelligence?

Last but not least, admitting answers to questions that no one has (yet) asked can also be a sign of intelligence.

Particularly intelligent people tend to question everything. They do not simply accept information, but analyze and examine it critically. This curiosity drives them to dig deeper and gain a more comprehensive understanding of complex topics. […]

Intelligent people often recognize patterns and connections that others miss. They see the big picture and wonder why others don’t notice these obvious connections. (source)

Admittedly, this approach is very pseudo-scientific and each of us would like to see ourselves in the role of the “intelligent questioner”. Nevertheless, the combination of misunderstood corporate culture, IOED, Rule of 10 and a certain human intelligence reveals an interplay that characterizes good employees and perhaps even more good leaders.

Asking questions is part of being a high performer:

The fact is, however, that asking questions or questioning things is a facet of high performers in the company. Good employees are …

[quote in german]

Excursus – When colleagues ask the right questions in a meeting:

Questioners are often ridiculed in meetings.

Yet it is precisely these ‘misfits’ or ‘wild ducks’ who move the company forward, safeguard projects and catch mistakes before they occur, thereby saving tangible euros.

It is important that not only superiors but also colleagues give these employees more space. Errors and problems that are discovered too late are often the main reason for hectic work, stress and overtime. Wouldn’t it be nice if someone opened their mouth next time instead of having to turn the whole project inside out two days before the deadline?

Overall, it is the task of managers to create an environment in which each individual can develop their full potential. This is the only way we can grow and develop as a company.

So the next time an employee comes up with a solution out of the blue, just send them for a coffee. Or: no whining, no progress. [german source]

Finding the right framework:

It may be that the problem is not with the employee or the general approach, but with the way the situation is being handled. It could be a manager’s job to encourage an employee to clearly state an approaching problem or potential misdevelopment. However, instead of discussing such issues immediately in the team meeting, the employee could be asked to structure their observations and concerns in a written (mini) report. This makes it possible to discuss the issue in detail in a separate meeting within 24 hours of the meeting – ideally before the meeting.

This approach not only takes the pressure off the team meeting [see meme], but also promotes the clear structuring and documentation of the employee’s thoughts. In a one-to-one meeting with the manager, this report serves as a basis for assessing the relevance of the issues raised. The manager can then specifically check whether the problems are actually serious and/or how high the risk of them occurring and the potential damage is.

Conclusion:

In summary, it can be said that leadership is more than just making decisions and setting goals. It’s about creating an environment in which employees can make full use of their abilities and feel encouraged to ask questions and contribute new ideas. Yes, it can be annoying in some situations when employees ask detailed questions. Countless memes tell of this.

Asking questions is therefore much more than just a form of communication – it is a business success factor. Asking the right questions early on in the project can prevent costly mistakes. At the same time, targeted questioning demonstrates competence, innovative spirit and strategic thinking.

But what happens if critical questions are suppressed in meetings? Committed employees who question things develop solutions and drive progress. However, if they are thwarted – whether by superiors or colleagues – this leads to frustration in the long term, reduced innovative strength and, in the worst-case scenario, an exodus of valuable talent. The result: rising costs due to fluctuation and loss of knowledge.

Instead of reacting to critical questions by rolling their eyes, managers should promote a culture in which questions are expressly encouraged. This is precisely where there is enormous potential – for teams, companies and successful projects.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs) about “Leadership: Answers to questions no one has asked”

1. why are employees who point out problems often seen as pessimists?

In many companies, employees are expected to think and act in a solution-oriented manner. Those who “only” point out problems without presenting a ready-made solution are quickly labeled as complainers. However, recognizing problems at an early stage can help to avoid costly mistakes.

2. Why is it important to clearly name problems instead of describing them as “challenges”?

The deliberate avoidance of the word “problem” can lead to actual difficulties being underestimated or not taken seriously enough. Problems can only be solved effectively if they are clearly identified.

3. What is the “Rule of Ten” and why is it relevant?

The “Rule of Ten” states that the cost of rectifying an error increases by a factor of 10 the later it is detected in the process. Asking questions and identifying problems at an early stage therefore not only saves time, but also considerable resources.

4. How can companies establish a culture in which critical questions are welcome?

Managers should specifically create an environment in which questions are valued and seen as a contribution to improvement. This includes rewarding employees not only for finding solutions, but also for recognizing problems.

5. What is “rubber duck debugging” and how can it help in the corporate context?

This method from software development helps to solve problems independently by describing them in detail – often symbolically in relation to a rubber duck. By consciously structuring your own thoughts, many problems can be solved before they have to be passed on to others.

6. What can managers do when critical questions disrupt the team flow?

Instead of discussing issues ad hoc in large meetings, it can be useful to encourage employees to structure their observations in short reports. These can then be further analyzed in individual meetings and discussed in the team if necessary.

7. Why are questioners often valuable employees?

Employees who ask questions scrutinize processes, uncover errors at an early stage and contribute to strategic development. Companies that promote these skills are more successful and innovative in the long term.